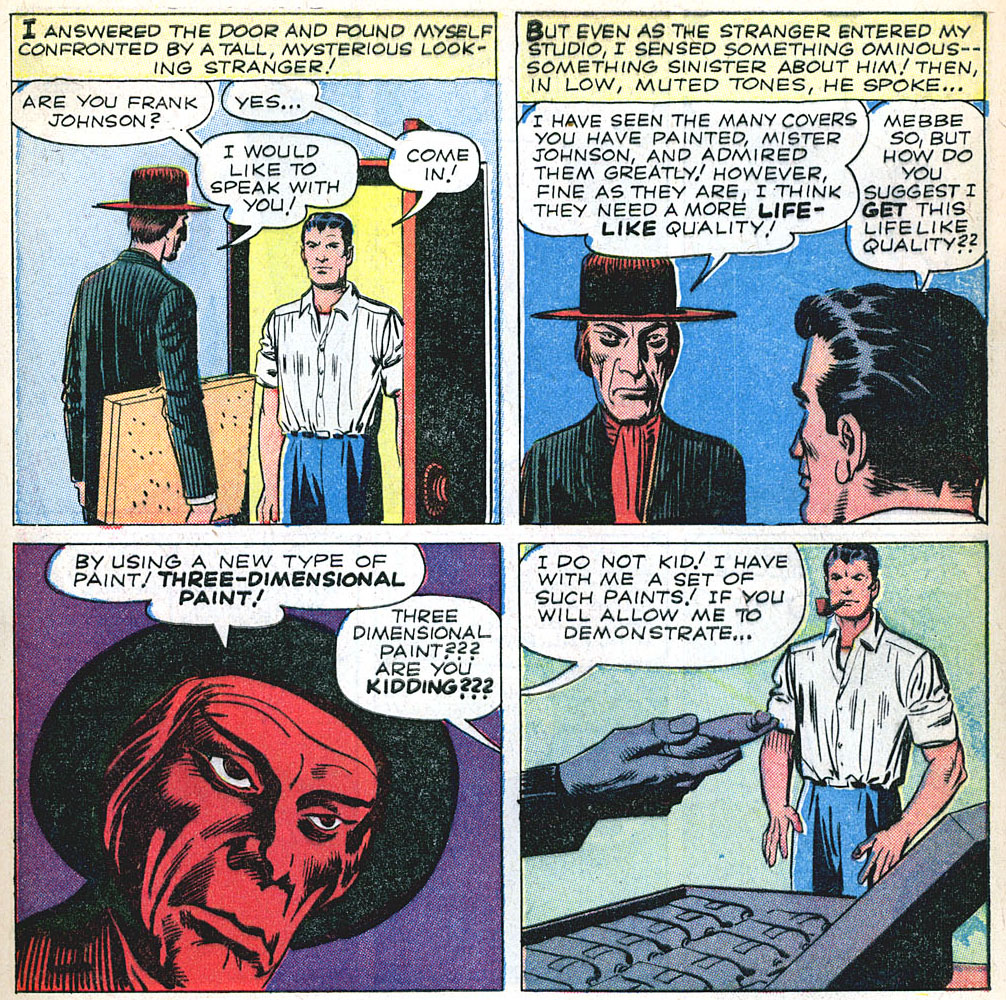

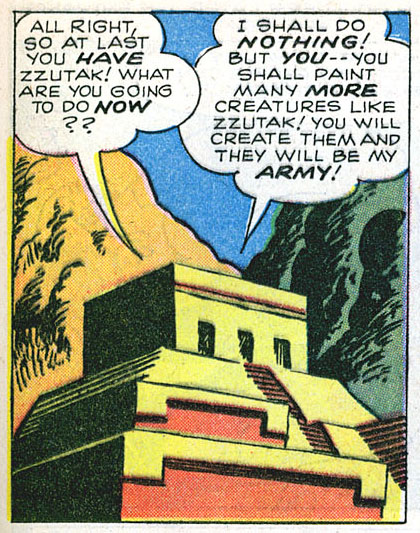

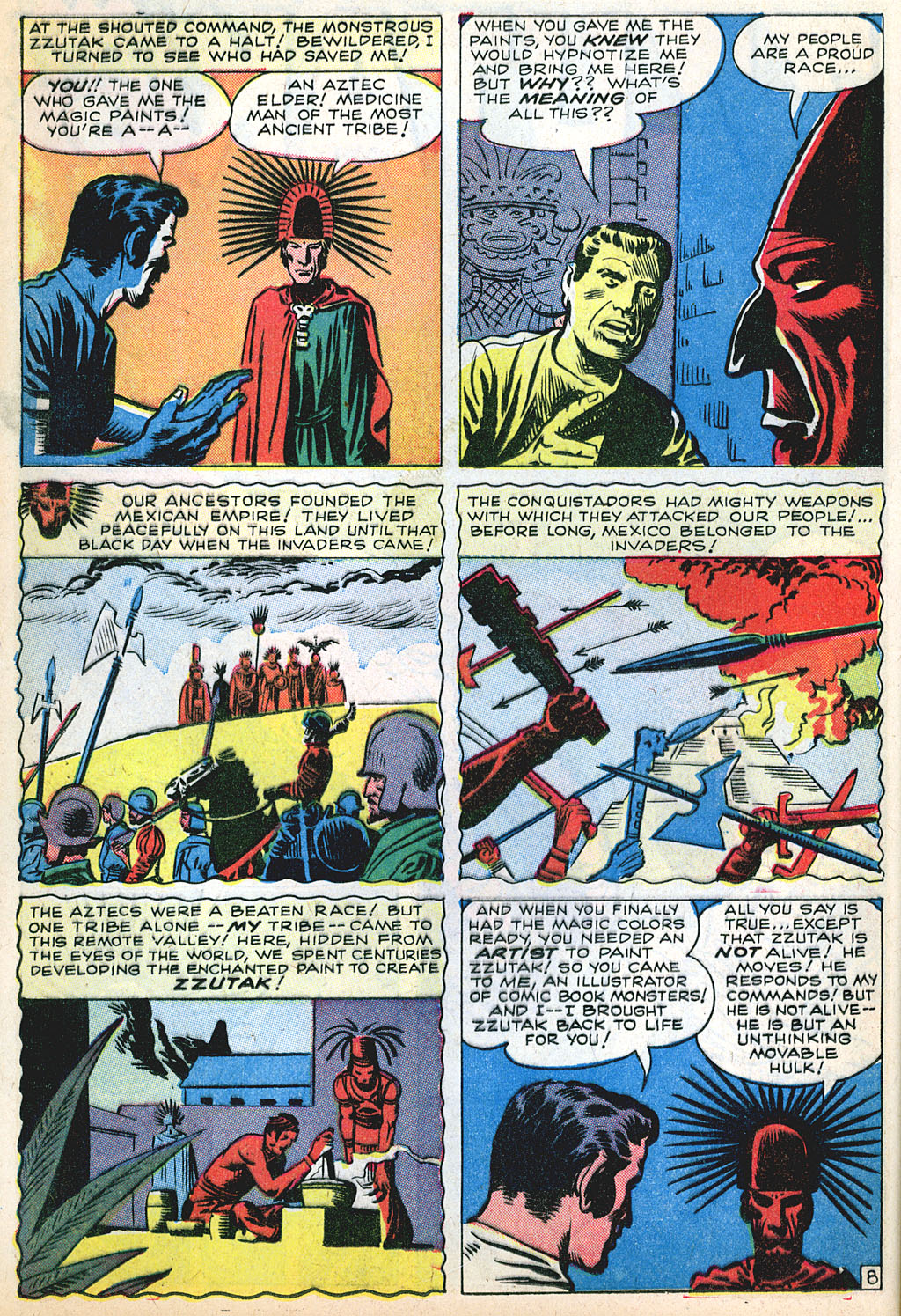

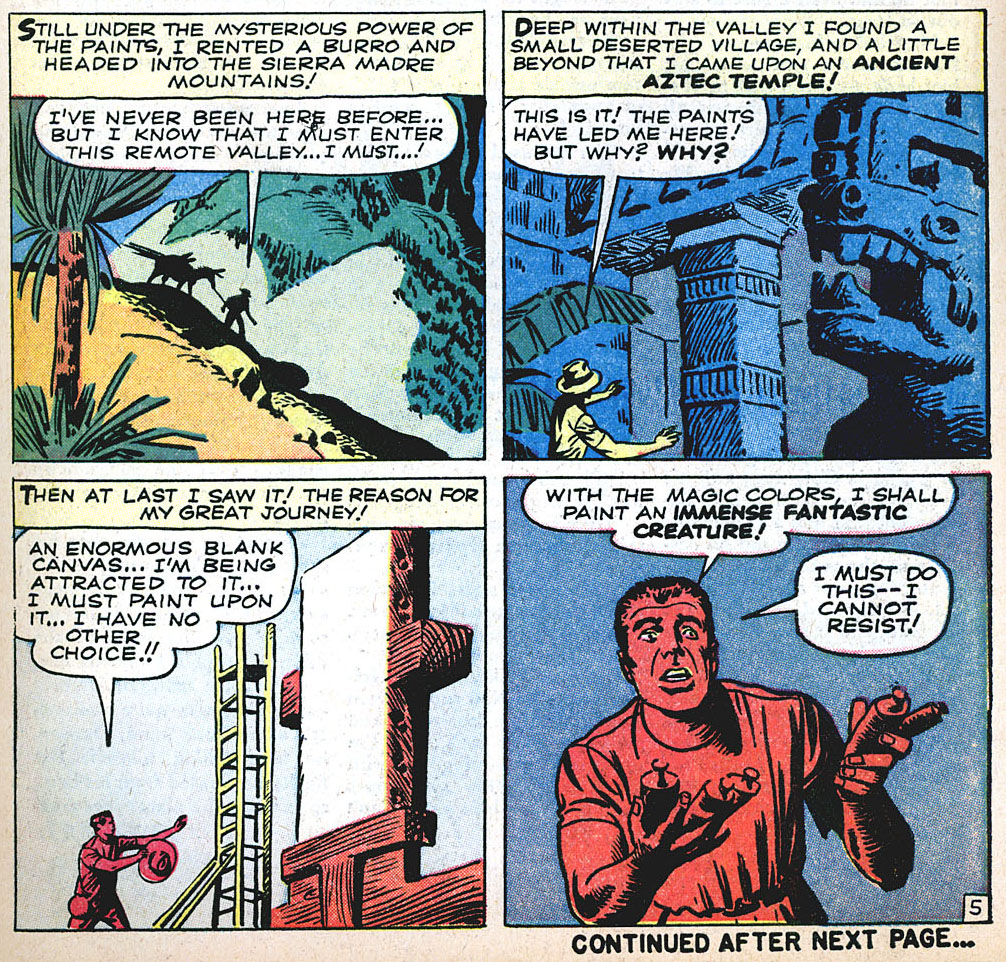

Issue number 88 of the anthology comic book Strange Tales features a two-part story called “Zzutak: The Thing That Shouldn’t Exist!!” The protagonist is a comic book artist who, celebrated for the imaginative monsters he has created in the past, is under pressure to come up with a new and even more spectacular creature for his next submission. Just as he sets to work, he receives a visit from a strange man who gives him three-dimensional paints which create images that seem to jump off the canvas. Convinced this is just what he needs to surpass his prior efforts, the artist is thrilled, but soon comes to realize he is under the spell of these hypnotic pigments, which compel him to travel to Mexico. Guided by this mysterious force, he arrives in a remote valley where he discovers a hidden Aztec temple and a giant blank canvas on which he begins to paint. Once finished, the creature he depicts—Zzutak—steps out of the canvas into the real world. As this happens, a mysterious figure appears and issues commands to the monster, which obeys him completely. This Aztec elder, revealed to be the same man who gave the paints to the artist at the beginning of the story, explains that after his people had been devastated by the Conquistadors, they retreated to this hidden valley where they spent centuries developing the magical paints that would enable them to create an army of mindless monstrous beings to carry out their revenge. Chosen for his past work creating fantastical monsters for comic books and now held prisoner by the warriors of a lost Aztec tribe, the artist is forced to paint further creatures. As he does so, he chants instructions to his newest creation that it is the enemy of Zzutak. When it steps out of the canvas it engages in violent battle with the other monster, eventually causing the destruction of the temple. Unable to stop this calamity, the Aztec elder is caught in the collapse, from which he emerges alive but having lost his memory. With their leader rendered ineffectual, the rest of the tribe gives up on their dreams of vengeance and unseals the valley. Before he departs, the artist burns the paints to stop them from being used again in the future.

As is so often the case, source material from a variety of cultures was combined in “Zzutak”—the “Aztec” temple is depicted with Zapotec architectural moldings from a millennium prior to the Aztec era, for example—to create a vague and generic pastiche of ancient American civilization. This suggests that, despite the specificity of place and tribal identity in the story, the Aztecs are intended to be synecdochic for all cultures of the indigenous Americas. Furthermore, the characterization of the Aztecs in this story follows familiar tropes, as they are depicted as both fierce and mystical. Beyond such broad stereotypes, the narrative of “Zzutak” contains a number of points that serve to demonstrate some of the ambiguities and contradictions that the mid-twentieth-century Euro-American imagination projected onto the pre-Columbian past.

The dominant contradiction expressed in this story relates to the Conquest. This genocide—the original sin of American colonization—is the source of white guilt. As it is recounted by the Aztec elder, his noble and peaceful people were destroyed by conquerors with superior weapons. Blame is not placed on the Spanish: those responsible are identified generically as “invaders,” which allows the conquest of the Aztecs to be extended to the conquest of the entire hemisphere by European powers. By giving voice to the dispossessed, the story thus expresses a degree of empathy with their plight and lays bare the barbarism at the root of—and inherent within—modernity. Yet if the story evinces guilt over the genocidal Conquest, it is also driven by anxiety that it was left unfinished. In a secluded valley, an Aztec tribe has escaped the twin forces of destruction and assimilation only to be driven by an all-consuming desire for vengeance. If their dream of conquering the conquerors is characterized as understandable, or even inevitable, it poses an existential threat to the current world order and therefore cannot be tolerated. Implicitly justified as self-defense, and with the Euro-American comic artist absolved of directly bringing about the destruction that results from the clash between Zzutak and his monstrous foe, the story ends with the crumbling of the Aztec temple, which serves both as the completion of the ruination brought about by the Conquest and the reinscription of its necessity.

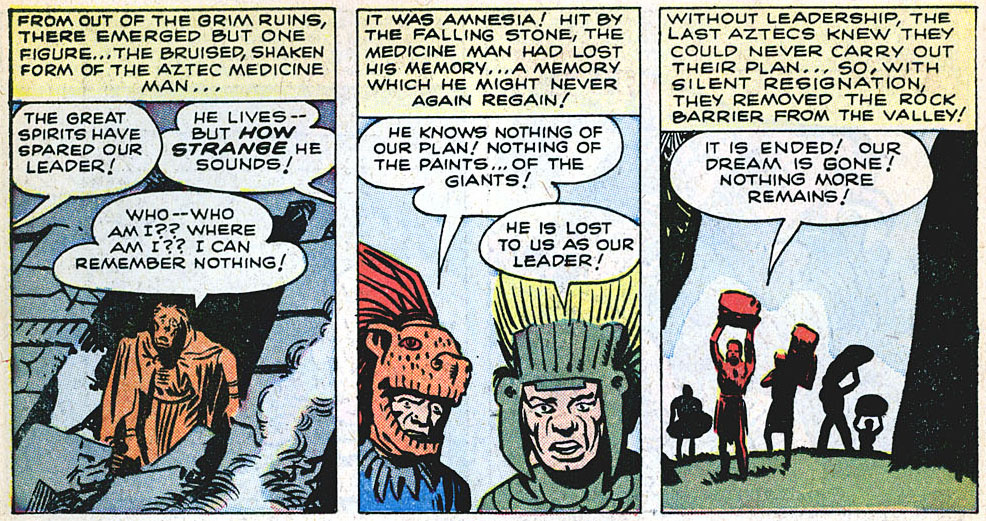

A further set of contradictions in the story has to do with the agency of the characters. With the help of the hypnotic power of the paints he has created, the Aztec elder is imputed to possess a supernatural control over the artist, whom he compels to act against his will. However, the reason why a civilization with its own significant artistic legacy, attested to in the sculptures seen in the backgrounds of several panels throughout the story, would need to seek out a painter belonging to a different culture is never adequately explained. Furthermore, the mystical hold over the artist seems to fail after Zzutak steps out of the canvas. He is compelled to paint the second creature because he is hostage to the Aztecs, not because his mind is controlled, and as he does so he is able to exert his own will into the monster so that it does not obey the elder. Finally, when the elder loses his memory in the collapse of the temple, the rest of the Aztecs immediately abandon their plan and free the artist, portraying them as lacking any agency to carry out their vengeance in the absence of a charismatic leader.

The ways the pre-Columbian past is characterized in the story of “Zzutak” belong to the context within which it was written. The outcome of the centuries-old Conquest is attributed to the technological superiority of the weaponry of the conquerors, resonating with the recent development of nuclear weaponry leading to the United States’ status as a world superpower. Additionally, the myriad hot conflicts of the Cold War were playing out in the global south, including in the countries of Latin America. The domination of these peoples was argued to be a necessary evil, preventing the incursion of political tendencies that threatened the foundations of Western capitalism. Read allegorically, the clashing monsters in the comic book can be understood to represent the dueling superpowers of the mid-twentieth century. Unstoppable and oblivious to their surroundings, their battleground is in the remnants of a civilization already devastated by centuries of colonialism and imperial subjugation, and this they leave in ruins, the final inhabitants resigned to their fate. Finally, the first time we meet the Aztec elder in “Zzutak,” he is comfortably operating within modernity, dressed in a suit and hat and able to pass as a cosmopolitan citizen of the United States. With feet in both worlds but driven by allegiance to his tribe, this figure reflects a fear of the unrecognized Other. In the cultural context of the Cold War, the incognito Aztec likely reflects a McCarthyist anxiety over the possible presence of Communist agents in America. Likewise, the elder’s ability to control the thoughts and actions of the artist manifests the fear that Communist sympathizers in the creative industries could act in ways to influence public opinion.