John Walter Scott (1907–1987) was a prolific American illustrator known for his pulp fiction covers. In the 1960s, he was commissioned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormon Church) to paint several large murals for their facilities. His painting Jesus Christ Visits the Americas (also called Jesus Teaching in the Western Hemisphere), completed in 1969, is a massive canvas of 47” x 121” that now hangs in the LDS Convention Center in Salt Lake City. It depicts a central article of faith of the Mormon religion: that, following his resurrection, Jesus appeared among the peoples of the Americas, themselves descendants of the Israelites, to spread his Gospel. Those who received his teaching were the Nephites, while a second branch of New World Israelites, the Lamanites, refused to be converted by their former brethren. The two factions eventually engaged in a war that the Lamanites won. Having met their destruction, the Nephites left a set of inscribed golden plates recording their history. These were revealed by the angel Moroni to a New Yorker, Joseph Smith, in the 1820s, and, with the help of a pair of stones (urim and thummim, which the angel provided and which possessed mystical power), he translated what would become known as the Book of Mormon. Joseph Smith was far from the only nineteenth-century Euro-American to posit Old World origins for the native peoples of the New World, most often as the Lost Tribes of Israel. However, his account, unique in being obtained through divine revelation, was by far the most detailed version, as well as the most successful one. Nearly two centuries later, after such theories have long been disproven through a variety of scientific evidence, adherents of the Mormon faith remain the only significant group to still believe these claims.

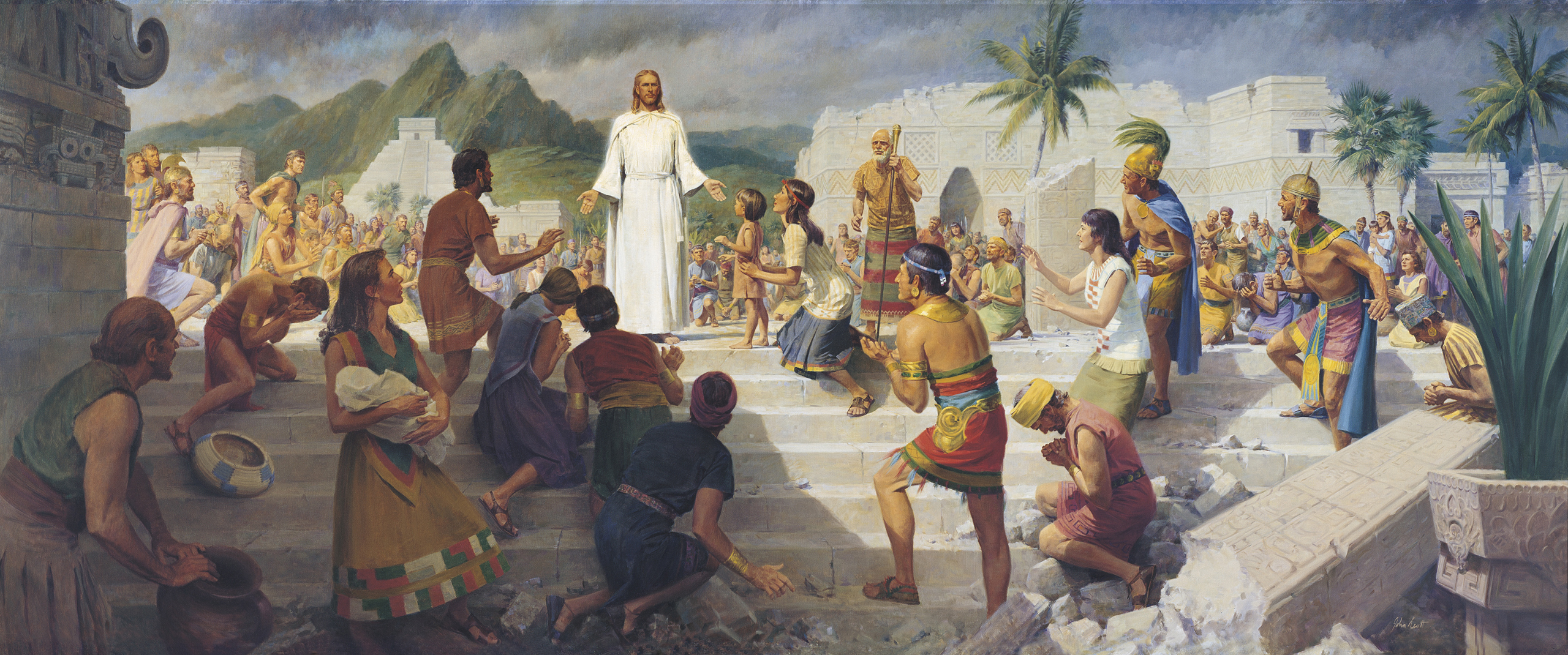

In John Scott’s painting, Christ occupies a central position. He stands in an open plaza at the top of a short, broad set of stairs, wearing a white robe and cape, and with his hands held slightly out from his sides to display the nail holes from his crucifixion visible to the crowd that surrounds him. The setting in which the scene takes place represents “Bountiful,” the name of the city-state identified in the Book of Mormon as the location of Christ’s appearance. It is shown in a semi-ruined state, reflecting the belief that a great cataclysm occurred at the time of the Crucifixion, with the sky turning black and the earth quaking. For the architecture itself, Scott largely followed Maya examples—including Puuc-style decorative elements and a stepped pyramid reminiscent of the Castillo at Chichen Itza—from Yucatán, Mexico, reflecting the common correlation of Bountiful with this region in Mormon thought.

This is despite the fact that these buildings were constructed hundreds of years after Christ’s purported visitation of the Americas, an anachronism mirrored by the Nephites’ wearing of golden ornaments, when metalworking didn’t come to the region until late in the first millennium CE. Indeed, many aspects of the costumes seen in the painting appear to be based on South American models, such as the crescent headdress of a figure towards the far left, and the tunic with an “Inca Key” design worn by the balding man to the right of center.

There are further aspects of the painting and its source material that complicate a simple geographic identification with a single place, including an architectural element from the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at the Central Mexican site of Teotihuacan at the upper left (placed beneath a Puuc-style deity mask despite these representing distinct architectural traditions separated by both time and space) and a flower planter at right that mimics the base of an Aztec sculpture of the god Xochipilli.

In terms of the landscape itself, the presence of high jagged mountains in the background of the painting have nothing in common with the flat karstic shelf of the Yucatan peninsula. The effect is a condensing of all ancient American civilization—and territory—into a single pivotal moment, whereby the appearance of Christ at Bountiful comes to stand for his evangelizing of the entire hemisphere. And while the Book of Mormon details numerous different groups or factions of First Americans, they are all claimed as descendants of the Israelites, thereby establishing a unitary basis for the characterization of all Indian people.

If the Book of Mormon asserted that the First Americans shared a common origin with all Judeo-Christian peoples, the Indians who were encountered by Europeans beginning with Columbus in 1492 were understood, according to Church doctrine, to be in a fallen state. Descendants of the Laminates, their dark skin was deemed to be an outward sign of their sinfulness, a curse by God for turning away from him. As Scott depicts in his painting, the Nephites, who remained in God’s good grace and who received the blessing of Christ, were conceived as having fair skin, as was Jesus himself. This explicit association between race and morality in Mormon thought had its origins with Joseph Smith in the 1830s, but the foregrounding of the whiteness of Christ and his chosen people in Scott’s painting should also be understood through the lens of the racial tensions of the late 1960s, a time when the Church was experiencing protests by Civil Rights activists protesting its discriminatory policies, which it sought to justify through theological grounds. Indeed, Mormonism’s tenets establish an ideological legitimization for the European domination of the Americas, beginning with the Spanish Conquest (as punishment for the sinfulness of the Lamanites) and continuing with 19th-century Anglo-American notions of Manifest Destiny (as the fulfillment of a promise of redemption to God’s chosen people).

The assertion that the significant cultural achievements and monumental remains of ancient American civilizations were actually accomplished by people from the Old World not only establishes a long Judeo-Christian lineage in the Western Hemisphere; it also, and more insidiously, refuses to recognize the creative agency and territorial claims of the indigenous population. With the exception of the Mormon Church, popular theories about the Old World, biblical origins of ancient American civilizations had largely fallen out of favor by the early twentieth century. Claims that Native American culture was based on knowledge obtained from outside sources persist, however. Rather than deriving from the Old World civilizations, this outside source of knowledge is now typically conceived as originating from extra-terrestrial or inter-dimensional beings. In this context, the selection of John Scott by the LDS to complete this painting (among others) seems uncannily apt. While he was likely chosen based on his cleanly legible and popularly accessible illustrative style, his wider oeuvre consists primarily of covers for adventure and sci-fi novels, including many scenes featuring aliens. As an example of imagery projecting magical explanations for the origins and achievements of Native Americans, it is not too much of a stretch to consider Jesus Christ Visits the Americas as part of the larger genre of pulp fantasy art that was the mainstay of the artist who painted it.

____________________________________________

For more on the ancient Americas in Mormon thought, see:

Evans, R. Tripp. 2004. Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination, 1820–1915. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Pasztory, Esther. 2015. Aliens and Fakes: Popular Theories about the Origins of Ancient Americans. Solon, ME: Polar Bear & Co.

On race and religion in America, see:

Blum, Edward J. and Paul Harvey. 2012. The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.